International and National Governments

For unidentified reasons, governments remained unconcerned with the climate issue until the late 1980s (Weingart et al. 2000). The little attention given to it mostly focused on short term consequences. It was not until the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was found in 1988 that national governments from around the world recognized a problem, and include the issue in their agendas.

IPCC

The IPCC is a scientific body, consisting of scientists and governments1. It was set up by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) to provide an objective source of information for policymakers about 1) the causes of climate change, 2) its potential environmental and socio-economic consequences and 3) the adaptation and mitigation options to respond to it.

It must be noted that the IPCC does not carry out research itself, but assesses the latest scientific, technical and socio-economic literature. Through extensive literature research, the IPCC produces – among other reports – Assessment Reports, which describe the current knowledge on climate change. The fourth and latest Assessment Report was released on November 17, 2007.

Integrity

Integrity

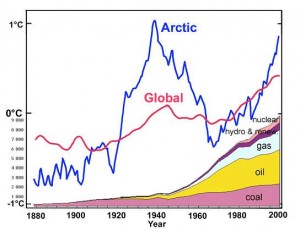

Although the IPCC shared the Nobel Peace Price with Al Gore in 2007, a number of leading scientists such as Syun-Ichi Akasofu, founding director of the International Arctic Research Center (IARC), question the IPCCs modes of operation. Akasofu accuses the IPCC for not looking at new evidence, which shows that it’s not CO2 that influences temperature, but temperature affects atmospheric CO2 levels (see for instance Pagani et al. 2005; Caillon et al. 2003). In addition, says Akasofu, the majority of scientists involved in the IPCC are meteorologists and physicists, rather than climatologists[1].

The IPCC based a significant part of their reports on results from computer modeling. Demeritt (2001) puts forth the IPCCs stance on climate modeling: ‘it is the most credible method for understanding, predicting, and thereby managing global warming’.

With the use of climate models, scientists try to prove that the rise in temperature from 1900 onwards is caused by CO2. Models are told that the warming of the last 100 years is caused by the greenhouse effect, and are then asked to calculate, based on the input given by scientists, what will happen in the future. Given the complexity of the earth’s climate system, it is impossible to incorporate each and every factor that influences the climate, and thus build a fitting model.

Furthermore, the climate models are created by modeling individual factors, and then combining every individual factor into one big model (Saloranta 2001). Understanding these models is only possible for a small number of expert modelers and physicists, therefore, the majority of scientists and policymakers have to presuppose that the modelers know what they are doing, and are reporting the whole truth. Moreover, by combining individual models into one big model, the latter will be prone to ignore any synergetic effects of individual factors.

In addition, many scientists whose work is adopted by the IPCC base their results on satellite data, rather then so-called proxy data: data collected from natural recorders of climate variability. Whereas satellite data is available from the 1970s, the entire history of the earth’s climate is obtainable from proxy data.

Because satellite data only covers the last 40 years of climate change, although it may be a valuable tool, by no means it should be used as the most important information source. Climatology deals with time periods of millions, if not billions, of years. Compared to that, 40 years is minute.

Surely, the IPCC is an organization that has excellent goals. However, it may be desirable for the IPCC to review their methods, and bear in mind that science is negotiation, and provides only provisional theories and answers.

The Dutch Government

The political discourse in the Netherlands started, in accordance with Weingart’s findings, in the late 1980s[2]. It was not until after 1990 that the Dutch government actively participated in setting up international and European goals for mitigation of and adaptation to climate change. The Netherlands Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and the Environment presented the first National Adaptation Strategy in the fall of 2007[3].

One of the main goals of the Dutch National Adaptation Strategy is to realize a behavioral change in governmental institutions, business corporations, societal organizations, and individual citizens[4]. To achieve this behavioral change, all parties involved need to become aware of the problem. According to the Dutch ministry, this can be accomplished by applying active communication strategies, which should help elucidate climate related risks. Secondly, the ministry hopes to assure that, based on demand, enough information is available and accessible. Thirdly, the ministry wants to support the adaptation process by adjusting laws and customs.

In this essay I will focus on how the government plans to raise awareness on the climate issue. The ministry wants:

- to engage in dialogues with the relevant parties, explaining what adaptation is, what can be done, and why we need to do it;

- to create a sizable platform for and active participation of the Dutch population in making the Netherlands climate proof;

- to provide clarity on who is responsible for what;

- schools to start focusing on adaptation from primary school onwards;

- to investigate whether it is possible to have insurance companies give people more money back for water-damages, floods and droughts;

- to reinforce the image of the Netherlands as a safe and economically appealing climate to settle.

This approach is tending towards transdisciplinary methods. However, from the goals stated above it is not clear whether lay expertise will be used for decision-making. The Dutch governments seeks to clearly inform the Dutch public, and have them actively engaged in dialogues or at forums, but doesn’t explicate whether these dialogues will be taken into account in the process of policymaking.

I argue that this is what the Dutch government ought to do: listen to what lay experts have to say. These lay experts may include normal citizens, business and media representatives, professionals, and other stakeholders. Lewenstein (2003) canvasses: ‘the lay expertise model assumes that local knowledge may be as relevant to solving a problem as technical knowledge’.

I believe it is important for policymakers to listen to every party involved, as it is for them that policies are made. Although it is noble of the ministry to want to inform people clearly and correctly, give them room for dialogue, and have them actively participate in obtaining common goals, I applaud a lay expertise model, rather than the contextual model proposed by the ministry.

[1] http://people.iarc.uaf.edu/~sakasofu/misleading.php

[2] Available from the VROM website http://www.vrom.nl/pagina.html?id=22990#b22072

[3] http://www.vrom.nl/pagina.html?id=34509&term=maak+ruimte+voor+het+klimaat

[4] From: Nationale Adaptatiestrategie – de beleidsnota

Leave a Reply