Scientific Uncertainty vs. Journalistic Certainty

The sci ence

ence

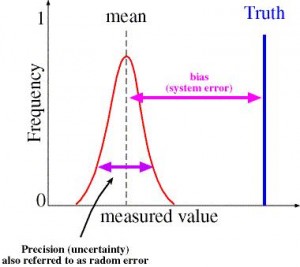

In principle, science can never prove anything. You can repeat an experiment 10,000 times, and conclude that something seems very probable, but you can never be absolutely sure that the same thing will happen the 10,001st time. A great help in tackling this problem is statistics, which determines just how probable a specific phenomenon is.

The principle is obvious when examining scientific literature. It is customary – at least in the natural sciences – to provide confidence intervals with the reported results, which account for the uncertainty that scientists deal with. It is not without a reason that many scientific articles end with sentences like: “Our results strongly suggest X, however, more research is needed.”

In reference to climate computer models, the uncertainty increases by at least a factor two. In addition to the uncertainty in the outcome, there is no certitude regarding the input variables. Putting together this fact, and the understanding that the output solely depends on the input, one can conclude that predictions or projections rendered by these models may be a useful tool, but should by no means be used as the primary method for “understanding, predicting, and thereby managing global warming”.

The journalism

In utter contrast with the uncertainty experienced and expressed by scientists, the media have been reporting findings as if they were as true as the Pope’s catholicism (Weingart et al. 2000). The reason for this is not hard to comprehend; a title such as ‘Cure for Cancer Maybe Found‘ would not attract a lot of readers, hence the paper will not be sold, the TV-program will not be viewed, and the radio will be switched to a different channel. Thus, media have to ‘translate hypotheses into certainties’ (Weingart et al. 2000).

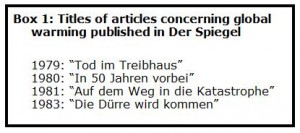

The most important hypothesis that is now commonly accepted by the broad public is that the anthropogenic increase of atmospheric CO2 is causing global climate change. A small number of titles that appeared in the German news magazine Der Spiegel are listed in box 1.

Another criterion for ‘good news’ is the relevance of the news for the individual (Hansen 1994; Carvalho 2007). This is conflicting in the climate issue, as climate timescales encompass periods of time that exceed our individual lifetimes. The media, however, reduced the climate timescale to a meteorological timescale, making the climate issue much more associable (Weingart et al. 2000).

A noteworthy aspect of journalism is selection. Subjects and views that appear in the press are not sought or found randomly. Moreover, journalists select their own sources, and, within those sources, select what information is passable. Thus, journalists and editors form a tight selection mechanism, only passing down information which they find suitable for us, the public.

Previous research as well as his own led Hansen (1994) to conclude that the images journalists have of their readers is hardly based upon surveys, rather, they are based upon the journalists’ perceived ability. This way, the people do not get the information they want, but journalists give people what they think the people want.

Although scientific consensus on the anthropogenic origins of climate change is indeed strong, a disproportionate amount of light is being shed on climate skeptics. Apparently, after 40 years of reporting on the risks of climate change, the media got updated on progress in the scientific community. They discovered a handful of skeptical scientists that openly doubted the extend to which the prevailing theories were true. This was novel and controvertible, which are also criteria for selecting what news to bring (Carvalho 2007).

In a recent study, Anabela Carvalho (2007) points out that 1) not only do the media give selective attention to those aspects that are novel, controvertible, and relevant to the individual, and that 2) the amount of media attention focused on climate change increases, but also that 3) the way in which the news is brought highly influences public understanding. Often, the seemingly innocent words the journalist chooses may subconsciously convince the reader or viewer of a fact that is not actually a fact.

Added up, one can conclude that the public by now must be quite confused: the scientific consensus that appeared so solid all of the sudden melts away, like snow in the sun. Indeed, a recent study (Stamm et al. 2000) shows that the media contribute to the misconceptions the public has regarding global warming. The same study, however, also pointed out that interpersonal communication is at least as important as mass media in conveying information. These findings suggest that a more (inter)personal approach to solving the misconceptions could be highly effective.

Leave a Reply